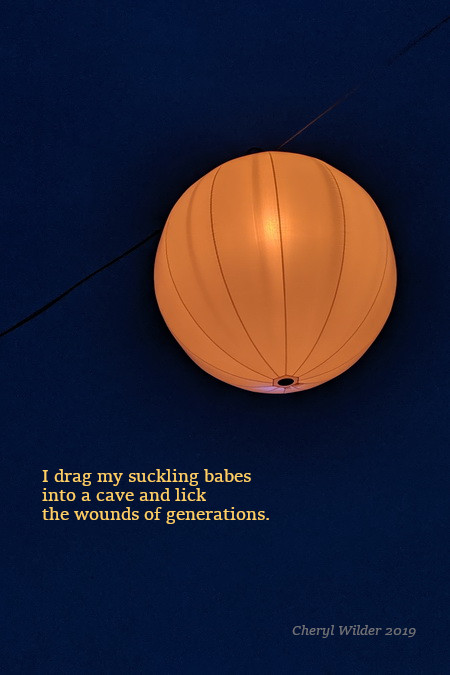

Poet Ralph Angel once said to a student: “I’m not interested in the story of my life. I’m interested in the fact of my life. The fact of my reality…any poet worth her salt…deals with their shit directly.”

In an interview with poet Gregory Orr, Krista Tippett said, “To talk about poetry is to talk about life.” Orr responded, “I hope so.”

In 2012, a friend and fellow alum of Vermont College of Fine Arts started Bite My Manifesto, a website designed to inspire. Here’s the beginning of my writing manifesto: “I started writing to grasp the chaos which is human nature. I kept writing to identify myself within said chaos.”

I’m interested in the fact of my life.

I started writing to grasp the chaos which is human nature.

To talk about poetry is to talk about life.

Pull up a chair and let us talk about life. Let’s deal with our own shit. As poet Lucille Clifton wrote, let’s celebrate:

something has tried to kill me

and has failed.

Poetry as Order

Why does talking about poetry mean talking about life?

The poet’s work is to put words to that which can’t be seen; to express that which leaves us, otherwise, speechless. To some, it might seem counter-intuitive that writing poems is an act of order–don’t poets spend a bunch of time frolicking? Yes. (At least I do.) But there’s also an unromantic side to poetry.

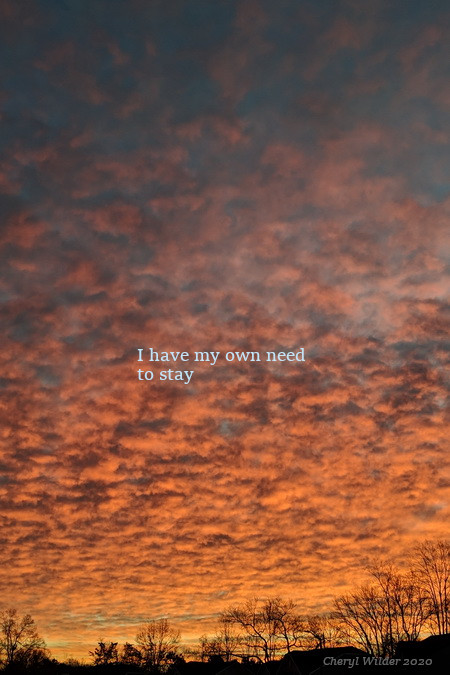

When I write, I take what is going on inside my body–questions, ideas, memories, emotions–and place it onto something tangible.

Once all the “stuff” is out of my head, I look at the written words and begin to shape them. I decide how I want readers to enter the poem; how much tension or rhythm or surprise; how long I want them to linger on a line or how quickly I want them to run down the page; where to pause and pause just a breath longer; lead them all the way to the exit–not an end, but a threshold they walk through, that may just lead them back to the beginning.

What started as a jumble of words, becomes a cohesive piece of communication. It’s as if I can see my interior landscape before me.

But that is the talk of poem-making.

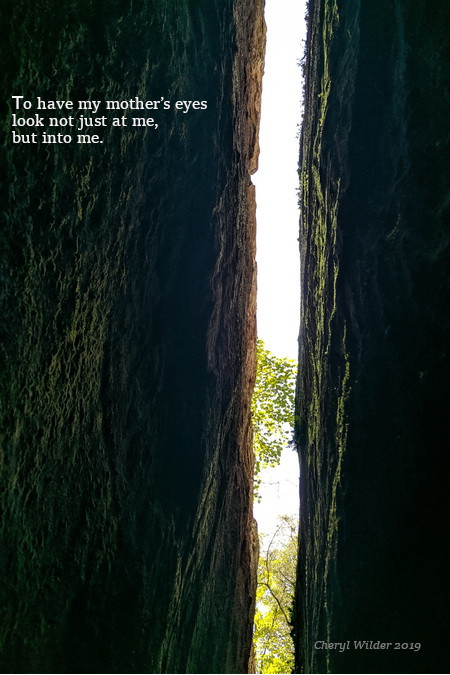

Order is also for the reading of poems. We reach for poems in times of need–to express our love or to give company to our loneliness. Poems help us order our interior landscape, not by providing direction but by reminding us we are not alone, and we have the strength to persevere.

To talk about a poem is to talk about the stirring and aching of the heart, the joy in a drop of rain, and the struggles of identity. Poems ask us to see ourselves in the words and also to accept that those words will outlive us.

In other words: You are poetry.

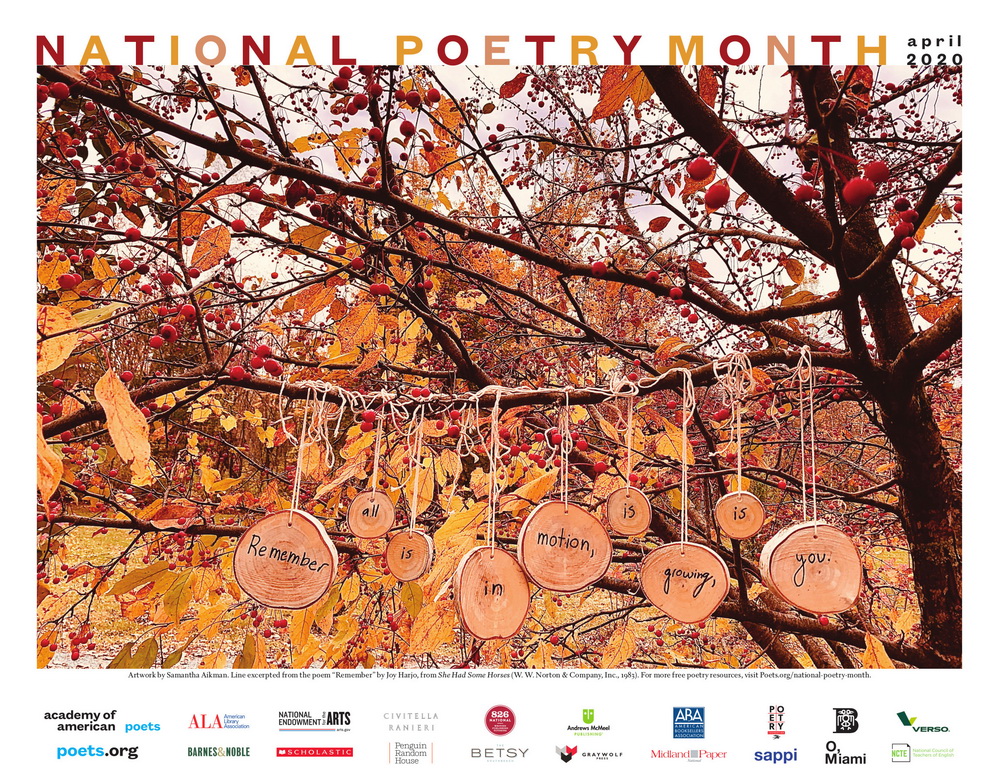

National Poetry Month

April is National Poetry Month. Maybe one day we will sit around the table together and talk about the stuff of life via poetry. Until then, here’s a few resources to get you started.

Poetry Unbound at The On Being Project – “Immerse yourself in a single poem, guided by Pádraig Ó Tuama. Short and unhurried; contemplative and energizing. Anchor your week by listening to the everyday poetry of your life, with new episodes on Monday and Friday during the season.” (Approximately 7 minutes.) For more poems and writing, visit their Poetry & Writing section.

Academy of American Poets: Sign up to receive a poem a day in your email. Learn more about Poem in Your Pocket Day. There’s teaching materials, a database of poems, and poems for kids.