In his book, Home: A Short History of an Idea, Witold Rybczynski says, “Before the idea of the home as the seat of family life could enter the human consciousness, it required the experience of both privacy and intimacy, neither of which had been possible in the medieval hall.”

The first time I encountered the concept of privacy was after my parents’ divorce. Mom moved, with my sister and me, from our three-bedroom house into a two-bedroom duplex. My sister and I shared a small bedroom that neither of us spent much time in except to sleep. As a seven-year-old, I was excited to have sleepovers with my big sister. At the age of eleven, she did not feel the same way.

We moved again, into a two-bedroom townhouse, and Mom gave my sister and me the master bedroom. With more space to move around, my sister hung sheets to divide the room in two, demanding her privacy. I couldn’t understand why she was so insistent on separating herself from me.

Then one day, she moved her stuff into our garage, leaving me in the large master bedroom with mirrored closet doors. Now nine years old, I would listen to Madonna’s first album and dance in front of the mirrors singing at the top of my lungs, “You just keep on pushing my love, over the borderline.” When I danced, I made sure to touch every piece of open floor space. I reveled in my privacy.

The Stuff of Home

What keeps me glued to the subject of home is it’s relation to the awakening of our interior selves. Rybzynski says this:

“Words such as ‘self-confidence,’ ‘self-esteem,’ ‘melancholy,’ and ‘sentimental’ appeared in English or French in their modern senses only two or three hundred years ago. Their use marked the emergence of something new in the human consciousness: the appearance of the internal world of the individual, of the self, and of the family. The significance of the evolution of domestic comfort can only be appreciated in this context. It is more than a simple search for physical well-being; it begins in the appreciation of the house as a setting for an emerging interior life.”

The word “home” in western culture comes from the Old Norse word heima, meaning “at home.” In its inception, the word encompassed the house and the household: dwelling, refuge, ownership, affection, the overall feeling of the place.

When I think of building self-esteem or self-confidence, the words used to define the meaning of heima make sense to me.

- I am my own shelter; when I turn inward, there is a refuge.

- As a source of affection, I am kind to myself, and therefore, self-reliant in times when I feel lonely.

- I am confident when I feel ownership over my body, emotions, and thoughts.

- In high school, I asked Mom for a scale. Her answer: “It’s not how much you weigh but how you feel about yourself.” She taught me to trust my overall feeling of the place. The place was me.

When I work to feel at home within myself, I simultaneously work on how I feel in a room, in a house, with other people, and in society. To build a home within me is to build a home within the world. I take refuge, affection, dwelling, and an overall feeling wherever I go. As my body changes with age, illness, or injury, it’s like moving into a new house; I learn the quirks of the structure; I make changes to represent the old me in a new space.

Privacy

My sister and I never had to share a room after the townhouse. I soon lost the large bedroom when we moved again, and never regained one of that size. But it taught me the power of space, solitude, and how to make my surroundings reflect my interior self. Not that I understood that intellectually at the time. But I carried the ideas with me thereafter; that room shaped a piece of my identity.

Intimacy

Intimacy, well that’s something that took longer to understand. Privacy is a physical construct. Walls of a house create a boundary between public and private. We go home and shut the door. If you share a room with your sibling, you hang a sheet.

But intimacy? The close familiarity of another person. As I reflect on childhood, that’s not so easy to pin down. Togetherness, affinity, confidentiality; how fickle those words feel in my adolescent memories. I had closeness with friends and, yes, felt attachment to my family. But when I look for a moment that awakened my awareness of intimacy, I think of my first comfortable silence.

I was a sophomore in high school. My neighbor’s bedroom was in the attic of his house and it had a skylight. He was two years older and whenever I went to hang out, his room was full of other friends. But one weeknight I went over and it was just the two of us. We talked, and then lay on the floor looking at the stars through the skylight, in silence. We weren’t touching; I only knew he was there by his presence. I felt my mind stop, like it does in meditation.

It’s easy for a teenager to feel pressure in high school; stress stems from so many different places. In the privacy of my neighbor’s room, all exterior influences were shut out. Inside the intimate moment that we created, I felt no coercion from him and no pressure from myself. I was at ease; present.

Moving my body across every inch of carpet in a childhood bedroom taught me the importance of having my own space and solitude; the comfortable silence taught me power in the space between two people.

I mentioned last month that it was ten years ago when I came to the idea that home is the space between two people. And it makes more sense today. A comfortable silence might be one of the more intimate exchanges between people; it’s an experience of refuge in both self and other.

Is there any better place to dwell?

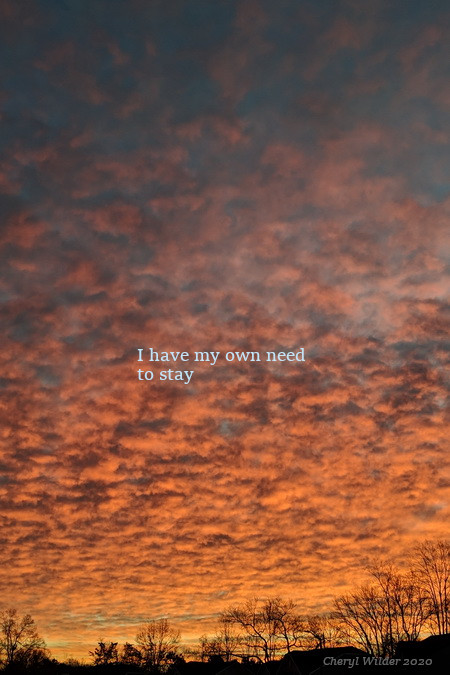

Excerpt from “Flood” in What Binds Us. Image was taken by the author. All rights reserved.