On Tuesday, March 23rd, I celebrated Anything That Happens with a virtual book launch. (Watch it here.) There were thoughtful, engaging questions from the audience. Due to time constraints, some questions weren’t addressed or didn’t receive thorough answers. For the next handful of blog posts, I’m going to answer these questions in more detail.

What does your writing practice look like now, when you put pen to paper?

My writing practice changed at the beginning of the pandemic. Before then, I primarily wrote on the computer. The pandemic prompted me to spend more time online, and I felt a pull to separate my creativity from the news.

I use a sketch pad with an Optiflow pen. When I don’t have an idea, I draw. Moving the pen around the page often opens me up. After I get a first draft, I transfer the poem to the computer. At some point during revision, I print and revise on paper. I read the poem aloud while walking around my office (or the upstairs bathroom when everyone is home). From there, it’s back and forth between the computer and a printout.

It took a while to learn that I need to move my body to create. I thought being away from the desk meant I was ignoring the work. But I need movement; gardening, hiking, yoga, dancing, and even cleaning. During the pandemic, I couldn’t do a lot of deep thinking. I relied on movement to keep my creativity flowing. Writing prompts are great, but I don’t often use them. I use movement to prompt me.

Do you write at certain times of day or in certain places? Or does it happen organically in bits and pieces?

My schedule has fluctuated over the years. During graduate school, I wrote mostly at night and on the weekends. When there were babies in the house, I wrote very little, if at all. Flexibility has been a consistent part of my writing practice.

A more consistent writing schedule came when my youngest boys went to kindergarten in 2018. I work part-time from home, which allows me time to write. I do my best generative writing in the morning, whether I start at 5:00 a.m. or 9:00 a.m. Writing also happens in bits and pieces. There are notebooks and pens all over the house, inside every purse, and stashed in the car. I strive to make the writing happen and to let it happen. No matter where I start a poem, I always return to the “workshop” to get the writing done.

It took decades for me to have my own office (with one exception in 2009-2010.), and it’s where I want to write. The exception is during final revisions or when I am stuck. While working on Anything That Happens, I went to Cup22 in Saxapahaw, NC, to revise. I also took mini solo trips to spend uninterrupted time working.

I don’t pull late nights writing anymore. Instead, I like to be asleep by 10:00 p.m. so I can start over again in the morning.

Writing Practice Summary

Movement – Keep the writing brain ignited while moving your body.

Flexibility – Adapt to life’s changes instead of fight against them.

Space – Find the space where you feel “at home” as a writer.

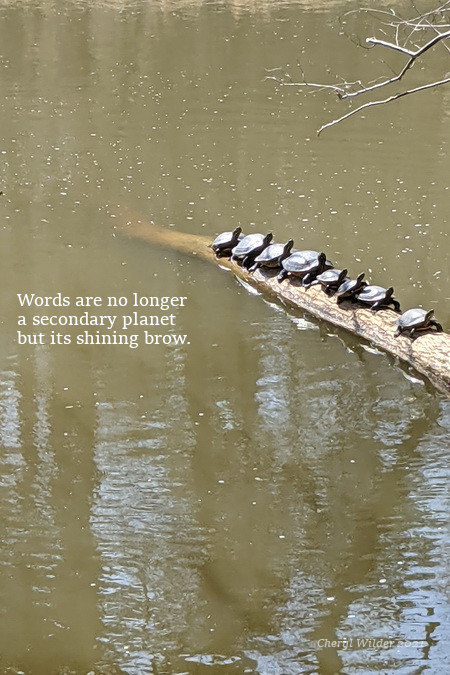

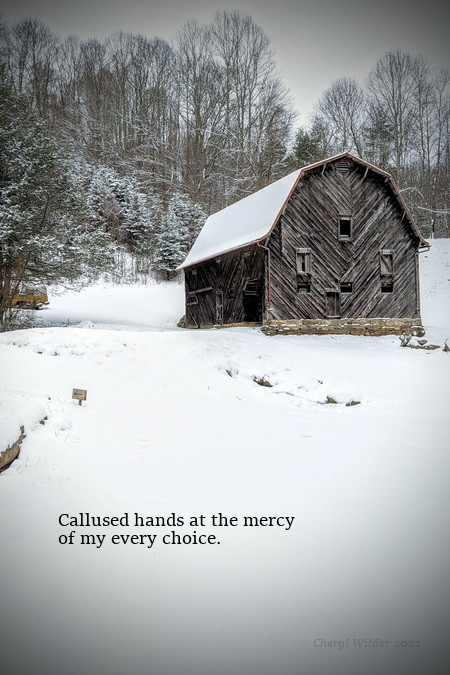

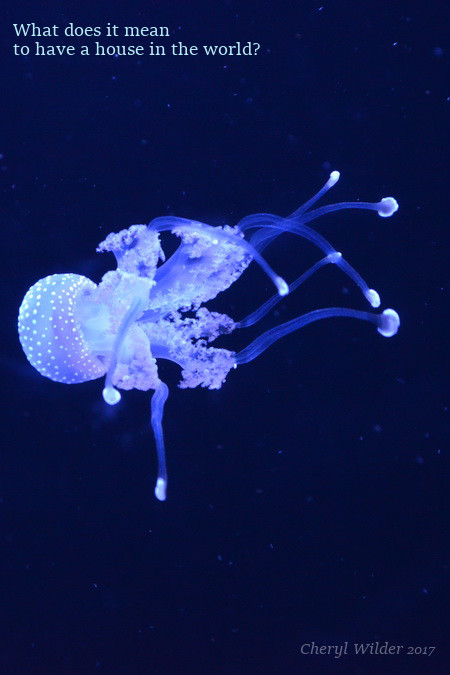

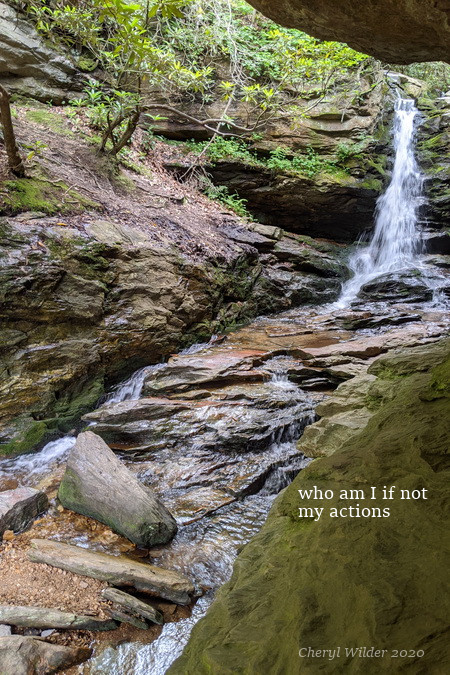

Quote and photo by author. (From “Moon Poem” in Anything That Happens.) All rights reserved.